Tyler Green on Carleton Watkins: Late George Cling Peaches

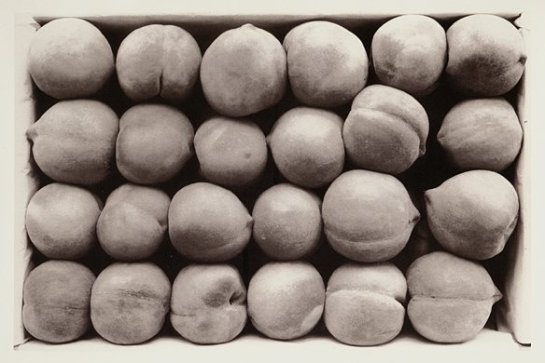

Carleton Watkins, Late George Cling Peaches, c. 1887-1888. Albumen print from wet-collodion negative. Courtesy of The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

As much as any of his more famous landscapes of Yosemite or Mount Shasta, Carleton Watkins’ Late George Cling Peaches is a masterpiece. The picture, in the collections of the Huntington and the Museum of Modern Art, New York, shows a box of peaches, a subject so paradoxically obscure and familiar, that nowhere in 19th-century art, neither in America nor in Europe, is there anything like it.

To put Late George Cling Peaches into its proper context, to understand why it holds our gaze, we need to go back 500 years. Since at least the thirteenth century, Western art has been significantly interested in how a two-dimensional medium, such as painting, might realistically present the third dimension. In the late 1200s, a Florentine painter named Giotto helped introduce life into art, or, as we might put it today, for painting people in a manner that was lifelike and that gave volume to the human figure. Around 1425, another Florentine, Filippo Brunelleschi, composed images of Florence’s buildings, its cityscape, using what would later be called ‘linear perspective,’ the painterly use of geometry to create a realistic simulacrum of depth, and a believable representation of reality. More simply, Giotto and Brunelleschi pioneered making paintings of things that looked less like an outline or a colored shadow, and instead look more like something real.

For most of the next 500 years, between the late dark ages and the dawn of modernity, artists tried to present depth more and more realistically. Typically art historians attribute the birth of modern art to the coming together of two seemingly unrelated artistic interests: Artists began to take contemporary life as a subject, and, once that turned out to be something fairly easily done — look, a cabaret! look, boaters on a river! — they made clearer their break with centuries of the past by now working to eliminate depth and perspective for which half a millennium of their predecessors had fought so hard. Steps toward this new idea are evident in the late 19th-century paintings of Cezanne and then in the turn-of-the-century paintings of Gustav Klimt, but the elimination of depth and painterly perspective reached its apex a few years later, when Henri Matisse led the way toward a colorful style known as fauvism and when Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque purged color from their work in a bid to birth cubism.

At least that’s how it happened in painting. For photography, perspective and the presentation of depth is a trickier question. While in the early days of the medium many photographers looked to painting for ideas and inspiration — Briton Roger Fenton, arguably photography’s first master, was trained as a painter, and it shows in his pictures — few took on the concerns of the painting avant-garde as their own. Instead, 19th-century photographers, be they portrait daguerreotypists, scientists or landscape photographers, concerned themselves with capturing images of what was before the camera and doing so as clearly and as attractively as possible. Sure, the artist composed the image to the best of his ability — some better than others — but depth or perspectival space wasn’t an issue for photographers the way it was with painters. It was just part of the camera-captured, chemically processed image.

In part, this was because the presentation of depth was effectively built in to photography’s early technologies. Early ways of making pictures, such as the wet collodion process which was dominant through the 1860s, often resulted in images wherein the objects or landscape that was further away from the camera printed ‘lighter.’ Voila: For photographers, the depth for or against which painters fought was created as the result of chemical inevitability. By the late 1870s, as cameras, lenses and chemistry improved, that effect was nearly eliminated and the distant background and the foreground often melded together in the finished image. While the foreground was now clearer and richer, the background was too, and typically it was every bit as clear and rich as the foreground. Many photographers hoped that the viewer would understand that the camera, and thus the photograph, would necessarily flatten the image, that the foreground would appear to be pasted onto the background, and that the viewer would use her imagination to conjure the space between what was nearest the camera lens and what was farthest away. While it’s not clear how many painters realized it at the time, improvements in photographic technology brought painters to where photographic technology already was. Or to put it another way, what painters were fighting to advance toward — the flattening of pictorial space — was effectively built in to photography from the early 1870s onward.

Which brings us back to Late George Cling Peaches. It is a photograph of peaches packed in four horizontal rows of six. A deep cleft runs two-thirds of the way around each fruit, nearly halving it. They are babies’ bottoms in a box. The photograph is so detailed, so precise, that you can see light wrapping its way around each individual peach, pausing between each slightly upraised pore before vanishing into the empty black space between each fruit. The edge of the photograph is the edge of the box in which the peaches were shipped, unless the edge of the box is the edge of the photograph. That flattening of pictorial space that technical advances in photography had built into the medium? With Late George Cling Peaches, Watkins defeated it, showed that a skilled artist could win out over the march of technology.

The picture is not just a masterpiece of formalism. Late George Cling Peaches was a picture the celebrated a late 19th-century miracle: man’s hubristic transformation of southern California desert, in this case Kern County, into fruit orchards.

A few years before Watkins took Late George Cling Peaches, Kern County was one of the hottest, driest, most inhospitable desert landscapes in America. A few years before that, it was an inland sea, covered in floodwaters so deep that steamboats were able to paddle through it. On one hand, these cycles of extreme weather had been going on for centuries and probably for millenia. On the other, the floods brought rich soil to the valley floor. Where there was rich soil, there was the potential for agriculture. This wasn’t lost on San Francisco businessmen who, after a couple of decades of benefiting from the mining booms in California and Nevada, were flush with cash and looking for places to invest it. They realized that if they could somehow control the rivers coming out of the mountains on either side of California’s central valley, if they could normalize and regulate the flow of water that created the floods and thus eliminate the hydrological extremes that had made even low-density agricultural settlement and agriculture in most of Kern impossible, that they could make millions. In short, they believed they could manage nature and make the desert bloom.

As a San Franciscan with close relationships to the wealthy men who invested in railroads and land throughout California, Carleton Watkins was engaged with these desert reclamation projects from almost the beginning. Watkins was especially close to the San Francisco land barons who controlled Kern. In the late 1870s, those men sued each other over Kern water rights. One set of partners, James Ben Ali Haggin and Lloyd Tevis, hired Watkins to make pictures that they could use in court to support their claims against the other team, Henry Miller and Charles Lux.2 The case eventually went to the U.S. Supreme Court and became a landmark water-rights decision. The most important outcome of the suit was that it effectively confirmed that Miller, Lux, Haggin and Tevis controlled the water supply for almost all of the agricultural land in Kern County, and by their control of water they controlled the future of lands much larger than that. Haggin and Tevis had plans for all that water: They plowed their capital into re-shaping their new land, moving rivers, building canals, and filling-in marshes and lakes.

This was no small project: Kern County is bigger than New Jersey. At first, as often as not, they got it wrong and powerful Sierra-snowmelt-driven floods destroyed their earthworks. They kept trying: The potential rewards were too great for them to give up. Eventually their engineers figured it out, and their irrigation projects played a key role in the conversion of California’s once-inhospitable Central Valley into the global agricultural powerhouse it is today.

By 1888, Tevis, Haggin and Billy Carr, their politically connected local land agent, had finally figured out how to make their 375,000-acre patch of Kern bloom. (That acreage is equivalent to about 500 square miles of land, an area equivalent to 11 San Franciscos.) They formed the Kern County Land Company, whose waterworks fed a series of large farms on which they grew crops such as alfalfa and grain, and raised cattle. That was all well and good, but Carr and Haggin realized that the fastest, largest profits could be made from land sales, from breaking up their massive acreage and selling plots to individual farmers. However, there was an obvious problem: There wasn’t anyone in Kern County to sell to. Before Haggin and Carr transformed it, the Southern Pacific Railroad hadn’t even bothered to build its San Joaquin Valley line all the way to Kern’s county seat in Bakersfield. The county was home to no more than couple thousand recently arrived Oklahomans, Texans, Louisianans and Mexicans. Many were seasonal laborers already employed by the Kern County Land Co. Kern was so hot and dry and miserable that no one really wanted to live there.

Haggin, Tevis and Carr understood that the settlement of Kern — and thus their profits — would have to come from the East and Midwest, the two parts of the country that had fueled Western migration for several decades. But how to convince potential farmers in Pennsylvania or Illinois to move west, to take a chance on a bold, never-before-attempted reclamation project in a recently former desert wasteland? Answer: Hire Carleton Watkins. There’s no surviving record of what Haggin and Tevis told Watkins to do, but the resulting pictures make it clear: Make Kern look like somewhere you’d want to live, raise your family and farm. Make it look like a safe investment, like a place you could raise both crops and your family.3 Sure there were plenty of other photographers they could have hired, including one in Kern who worked for half of what Watkins charged, Haggin and Tevis knew how good Watkins was. He was money well-spent.

Part of the reason Watkins was a great artist — and part of why his life’s story and work are so fascinating — is that he had a particular skill for composing chaos into inevitability. No body of work demonstrated this skill better than the hundreds of photographs he made of Kern County. Here Watkins’ pictures would transform Kern’s withering desert and hydrological extremes into the land of cornucopia that Haggin and Tevis needed it to be.

In today’s terms that would make Watkins little more than a maker of slick marketing images, a PR-motivated shyster. But in the 19th century, that was de rigeur. For decades, American painters had cranked out idyllic landscapes, pictures that were too perfect to be real. If the land was blessed by Providence — and Americans believed that their place on the continent surely was — artists had to make the land look Providential. Watkins knew that his pictures had to fit an ideal, but he was a Westerner, more interested in serving capital than in serving the Lord. In Watkins’ Kern, the landscape wasn’t prepared by the Lord in advance of manifest destiny, it was built by man. That made Watkins the perfect artist for his time, and also the ideal artist for his clients and customers, railroad titans, land barons and bankers, men whose livelihoods depended on presenting the West as tamed, as a place safe for investment and relocation. In Watkins, modernity always wins.

Late George Cling Peaches is either the first or more likely the last of as many as nine pictures Watkins took of Kern orchards between 1881 and 1888. While it’s impossible to know exactly how Watkins intended the pictures to be seen, the way he numbered his pictures suggest that Late George Cling Peaches is the culmination of a group of pictures meant to be considered as a narrative. The first picture was probably an 1881 view of the Kern River as it exits the steep foothills of the southern Sierra Nevada and enters the central valley. Watkins’ message: There is a lot of water here, and there will continue to be, because the mountains and their snowpack provide it. The next several pictures shows the Kern County Land Co orchards, from a distance, then close-ups of an individual tree, a branch heavy with fruit, then on a cluster of peaches. The final image is the boxed peaches, likely shipped to Watkins’ San Francisco studio for photographing, just as they’d be shipped to Chicago or New Orleans for consuming, were intended as evidence of how you, a prospective migrant to Kern, could make farming in Kern pay off.

In any context, Late George Cling Peaches is an astonishing picture. How did Watkins make each individual fruit look so soft? Just as remarkable as the intensity of Watkins’ image is that it’s impossible to tell whether the box is lying flat with Watkins’ huge mammoth-plate camera above it, pointing down into the box, or whether the box is on end, across from Watkins’ camera.4

One way or another, the peaches are stuck in place, on a grid. Here, in 1889, Watkins has built a picture around a grid and by so doing has flattened space in a way that the European avant garde, which had been slowly, steadily working toward this — and toward the grid — since late impressionism, wouldn’t achieve for another 20 years. Another major innovation of modern art was that it made everyday life, the commonplace, into a subject of high visual art. What could be more ordinary than a box of peaches? One measure of Watkins’ importance as an artist is that he was alone among American artists of his period in making the seemingly mundane a subject of intense compositional experimentation.

Huntington photography curator Jennifer Watts has called Late George Cling Peaches “the first “modernist masterpiece.” The only other known copy of the picture is at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, for whom photography curator Sarah Meister acquired it in 2010. “If I died tomorrow and I never brought another work into the collection, knowing that Late George Cling Peaches is here, that’s certainly my proudest accomplishment,” Meister told me after installing the picture for the first time. “You can’t look at Marcel Duchamp the same way after seeing that Watkins picture. I think it radically changes how you see the nineteenth century, which then reverberates through the present.”

Tyler Green is an award-winning art journalist and the producer and host of The Modern Art Notes Podcast, America’s most popular audio program on art. He is writing a book (UC Press) on Carleton Watkins, the greatest American photographer of the 19th-century and arguably the most influential American artist of his time. The Huntington is home to the one of the most important collections of Watkins’s work.

This post was originally published on the ICW website in September 2015.

———————————————————————-

Listen to the recording of In Conversation with Tyler Green (Wednesday, May 27, 2015):

Carleton Watkins in California: How an Artist on the Edge of America Impacted American Science, History and Business