Reckoning with a Settler Historian.

Or, Why I Struggled to Write about James Miller Guinn

Laura Dominguez

Americans passed another year by toppling monuments and denouncing ghosts.

The violence that swept Charlottesville, Virginia in August 2017 burned public symbols of white supremacy into the American psyche. Those who still cling to these material objects under cover of “heritage” find themselves defending historical persons, events, and ideas at odds with prevailing notions of what is right and just in our time. Others charge that preservation of racist monuments, placenames, and other markers masks maintenance of oppression. The power to interpret the past in the public square has rarely belonged to the disenfranchised.

Spurred by violence against Black and Brown people, activists dragged monuments to the ground, splashed them with paint, tagged plaques, pitched statues into bodies of water, and performed ancestral rituals in emptied spaces. These spontaneous heritage practices are global, occurring in far-flung places where people have long resisted state violence and colonization. We witnessed them again after the police murders of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, and Breonna Taylor. These killings reawakened a beleaguered public to the realities of systemic racism in the midst of a worldwide pandemic that especially ravaged the bodies and lives of the marginalized.

An issue at the heart of these events is the definition of “heritage” itself. While heritage policies and practices in the U.S. have long privileged material and aesthetic values, local jurisdictions are beginning to explore what community practitioners have long known: that all heritage is intangible, dissonant, and affective. Heritage scholar Laurajane Smith describes it as “a cultural and social process which engages with acts of remembering that work to create ways to understand and engage with the present.”[1] Heritage is experiential and emotional, forged through social relations that help us make sense of our identities, feelings of belonging, and roles as civic actors. It is a performance, a form of negotiation that takes place. We might see the action in our streets as an emerging counter-heritage of anti-racism, a new, yet deeply rooted strand of resistance that challenges received wisdom about the past and suggests new commemorative possibilities.

In Los Angeles and elsewhere in California, Fr. Junípero Serra is an obvious target. A year ago, members of Tongva, Chumash, and Tataviam tribal communities gathered at the eastern edge of El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument, where a statue of Fr. Serra stood. It took twenty people to pull the figure to the ground. Organizers paired the toppling with a blessing ceremony, expressing solidarities among Indigenous and Black communities in resistance to, and healing from, the violence of white supremacy. The event was yet another milestone in the battle over the missionary’s legacy, which grew with efforts to canonize him beginning in the mid-twentieth century.

Long revered as the “father of the missions,” Fr. Serra represents one figure among many in Los Angeles whose legacy demands re-contextualization. Having inherited colonial methods of marking and preserving heritage, our civic leaders now seek repair. In late 2019, the mayor’s office convened a working group of scholars, architects, artists, writers, organizers, and city staff to reimagine how the city acknowledges and engages with our past. This year-long effort wrestled with a paradox of L.A. history, how a city that promises reinvention might also steward its past. The group’s recommendations shift the city’s role from gatekeeper to facilitator, asking how institutions “that so often trampled on community memory [might] reconnect with histories of Los Angeles that are smaller, less predictable, and less subject to top-down or official control.”[2] Now more than at any other time, the city is contemplating justice in how it remembers.

These questions fuel me. I study how different generations of Angelenos have reckoned with the past through the places that matter to them. I think of everyday buildings and landscapes as archives of dissonant memories. I am drawn to places where marginalized peoples resisted white settler efforts to erase them from land and story; where Black, Indigenous, and immigrant communities repaired connections to their ancestors and to one another. Put another way, I strive to understand the forerunners of today’s “statue abolitionists.”

Like my peers, I’ve struggled to find seeds in the archives over the last fifteen months. The pandemic changed how historians access our sources. Unable to visit physical collections, we turned to digitized materials. I found myself reading nineteenth-century tomes about Los Angeles, written mostly by white men (and a few women) who were complicit in building and maintaining an exclusionary society. Their voices are not the ones I hoped to encounter in the early stages of this project.

Yet reading their words helps shift attention from objects to process, away from the monuments themselves toward their makers. It’s a necessary first step.

***

This is how I met James Miller Guinn. It was a turbulent introduction. At first glance, his essays about L.A. revealed him to be an architect of well-worn racist narratives about so-called vanishing Indians, languid Mexicans, and enterprising Euro-Americans. His stories have long saturated our civic memory.

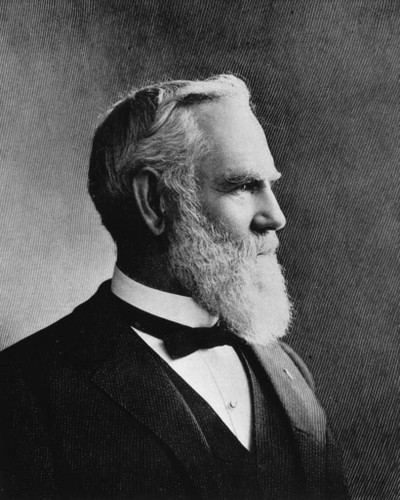

Born in 1834 to Ohio settlers, Guinn trained as a teacher at Oberlin before volunteering for the Union Army in 1861. He saw heavy combat during the Civil War. Like many veterans, he repaired to California for his health when his service ended. Following a brief chase after gold in Idaho, he settled in Southern California in 1869 and resumed his livelihood as an educator, reformer, and historian.

Despite my initial misgivings, Guinn became a useful emissary taking me back. I wondered if he was a window into the eyes of post-Civil War westward settlers who pinned hopes on Southern California, just as their forebears had done with the Old Northwest territories. What of their ancestry and heritage did Guinn and others bring with them to California, despite their belief in an Edenic rebirth? Did they believe that they were importing a historical sensibility to California that did not yet exist?

J.M. Guinn was a man of institutions. In 1883, he became a founding member of the Historical Society of Southern California (HSSC) and one of its more prolific writers. He advocated safeguarding the state’s heritage, especially its artifacts, buildings, and documents. “Literary pot-hunters and curio collectors” were robbing California of its “historical treasures,” he fumed, and the state had fallen behind other western states and territories in collecting and displaying its history.[3]

Guinn knew Los Angeles was changing. An irony of his quest to remember is how little twenty-first century Angelenos know about him and his fellow HSSC founders.[4] Within his lifetime, the 1876 arrival of the transcontinental railroad ushered in a real estate and population boom and placed new pressures on existing residents. Guinn feared the exuberance of newcomers for mythic tales of California would hasten historical amnesia, warning vigilance against “fads and fakes.”

Guinn argued that settler societies had a civic obligation to preserve historical materials for posterity. Investment in public history distinguished Anglo American settlers from Spanish and Mexican colonists and Indigenous peoples.

Guinn’s case for historical societies rested on the trope that California was an exceptional place. He pleaded with an audience of white citizens, politicians, and keepers of the public purse. “Wisconsin, with less wealth and half a century less history, has spent a million dollars on her historical building and library,” he charged. “When Kansas and Nebraska were uninhabited except by buffaloes and Indians, California was a populous state pouring fifty millions of gold yearly into the world’s coffers.”

Guinn believed white settlers were the makers and authors of official history. His grief for the disappearing heritage of early American conquest did not extend to losses of Indigenous or Mexican heritage. He ignored the city’s African heritage altogether. He borrowed sentiment from Frederick Jackson Turner’s “frontier thesis,” betraying anxiety over the so-called “end” of the epoch of western expansion. If the closing of the frontier demanded commemoration of nineteenth-century tales of exploration, settlement, and vanquishment, California seemed to be falling behind in the race to remember. Historical societies were not merely private institutions maintained by a few scholar-citizens, but a measure of the health and fixity of the settler state. Surely that endeavor was worthy of public funds, Guinn insisted.

Guinn envisaged the gratitude future scholars of Los Angeles would feel for the HSSC. Preservation was sacred work that few could pull off. Yet for all its ambition, the HSSC was a humble organization. Its origins in a “dingy and smoke-begrimmed” room of Temple Block, doubling as a courtroom for “tramps and drunks and other transgressors,” embarrassed Guinn.[5] The building where they debated and labored mattered. Ideally, it would legitimate this coterie of settler historians, those charged with drafting creation stories for the new colonial regime. Their words helped justify the erasures of bodies and knowledge and normalized the rights of white settlers to seize land.

Sensing how deeply Guinn wished to leave his own mark, I sat with several of his essays for a few weeks. I looked for him in the footnotes of other scholars, hoping to understand the influence of his ideas. In addition to his ruminations on historical authenticity, preservation, and conquest, I was struck by his attention to Los Angeles’s built heritage and the connections he drew between discipline and place.

Guinn’s essays about the built environment exposed his attention to darkness. If contemporaries like Helen Hunt Jackson and Henry Dwight Barrows introduced Americans to sun-drenched adobe courtyards, Guinn revealed where violence and punishment took place. For example, readers expecting a tour of great architecture in his 1896 essay “Historic Houses of Los Angeles” first had to wade through his reflections on prisons and lynchings. He described in detail two structures – the “Cuartel Viejo” and the “Nuevo Cuartel” – which both served double-duty as military quarters and jails for lawbreakers and political prisoners.

Constructed in 1786, the old jail crumbled as U.S. immigrants arrived in the 1830s. Guinn surmised that “the hateful memories of it that still cling to the minds of some of its former occupants may have hastened its decay.”[6] A one-room adobe prison replaced the old in 1841. Guinn noted that a local vigilance committee, having “delegated itself the authority to relegate the morals of the town,” liberated many a prisoner. Liberation, of course, lasted only as long as an escorted walk to the hillside gallows or the nearest gate post or crossbeam.[7]

The historian seemed reluctant to judge the brutality of earlier decades. Though he reiterated the racial thinking of his era, I detected hints of regret. These carceral landscapes meant something to him, even as his fellow Anglo Angelenos built new symbols of modernity and civility atop them. He nodded to the contingencies in civic narratives, that the gallantry of the Mexican pueblo and the progress of the American city relied on punishment. The adobe sites he eulogized were palimpsests of light and dark, a messy heritage of past lives that set the tone for what would rise in the future. Tempering his belief in reinvention, he wanted his readers to see these ghosts when they set foot on the streets. Jails, it seems, had a palliative effect on settler psyches.

Along with memoirists like Horace Bell, Guinn placed and corroborated a heritage of violence in nineteenth-century Los Angeles. He articulated a repertoire of vigilantism – the oaths of vengeance, the courtroom theater, the processions, the public spectacles, the narratives of justice served, the burials – all rehearsed and performed again and again.[8] As historians John Mack Faragher and David Torres-Rouff both argue, mob rule in 1850s Los Angeles served to reconcile or balance the score among Anglos and Californios whose social bonds bore signs of fracture in the wake of conquest. Put another way, extrajudicial violence was a reparative practice within a fragile, inter-cultural community of Angelenos. It revisited a past moment of civic rupture and carried out an irreversible form of redress to restore honor to those wronged. It reminded participants of their mutual understandings, shored up their identities, validated their belonging, and reactivated social relations. And it was adaptable. When, for example, Anglo and Mexican Angelenos massacred Chinese immigrants in 1871, they performed once more their co-created heritage of violence as a way of adjudicating racial hierarchies.[9]

The authors of these early histories didn’t suggest reviving the practices of an earlier generation. They didn’t need to, not when these rituals explained how modern Los Angeles came to be. When Guinn constructed the scaffolding of Los Angeles’s civic memory, he made sure that violence was one of its posts.

***

These were the thoughts that flowed from my initial readings of Guinn and his peers last fall. In the short term, I was charged with writing an op-ed about Guinn, placing myself in his intellectual lineage. To wander about 1880s Los Angeles and see who else was asking questions about civic memory. But I couldn’t do it. Not in that form.

To write a successful op-ed, I needed to find something newsworthy about Guinn. Reeling from the tumult of last year, I tried to bring him into conversations about monuments, museums, preservation, and civic memory. But every time I tried to put words on the page, I stumbled.

The rituals and demands of Black and Indigenous protesters were clear. American cities have dedicated enough time and space to historical figures who enacted and maintained white supremacy, without meaningful context and reappraisal. To be blunt, if I respected protestors’ goals and found meaning in their practices, why was I trying so hard to come up with 800 words about another long-forgotten settler? I argued with myself for a month.

The problem was that figures like Guinn have maintained their clout over public commemorations of the past for far too long. Why should I dedicate more room to their triumphant and exclusionary versions of history? These early historians were devoted to the settler colonial project of seizing land, dispossessing its inhabitants, and crafting a folklore of Anglo dominance. In a local context, they helped construct what Smith terms the “authorized heritage discourse.” They wrote historical scripts and claimed the moral authority of eyewitnesses and truthtellers. We yet find their fingerprints on our institutions, local governments, civic practices, and historical monuments.

This is not to say that civic memory has been stagnant for 150 years. Rather, I argue that practitioners engaged in “official” forms of memory work haven’t yet escaped their historical framings and ways of reading cultural landscapes. We’ve normalized their ideas and forgotten about them as people. We still maintain what they settled.

We are long overdue in listening to other makers of civic memory. To make the case for a more just approach to civic memory today, I want to learn from those who rejected these official stories and discourses over the last century and a half. The people who inscribed their own versions of the past into civic spaces, despite efforts to marginalize them. Or who made their own places for storytelling and remembering. In so doing, I believe, they began a process of healing or repair for their communities.

Many of these protagonists are still elusive, leaving me with J.M. Guinn. I decided it was time to meet him beyond his words and laments.

***

A few miles from my home is Angelus Rosedale Cemetery, where many of Los Angeles’s early residents take their final rest. Today, the graveyard falls within the boundaries of Pico-Union.

The Rosedale Cemetery Association dedicated the cemetery in 1884, postdating the Historical Society of Southern California by a single year. The two institutions shared the goal of commemorating the greatness of Angelenos. Rosedale’s directors sought to modernize the burial industry on the outskirts of Los Angeles, giving families an alternative to the crowded graveyards in the city center. They made the radical decision to open the cemetery to anyone who could pay the burial fee, regardless of race, religion, or socio-economic position.

The cemetery’s design captivated the living. Los Angeles Times co-editor Eliza Ann Otis declared in 1892: “What a beautiful city of the dead is Rosedale Cemetery, with its broad circling driveways, lined on either hand with graceful palms; with its emerald expanses of lawn, its growing flowers, pouring out their rich perfume, and its many elegant and stately monuments of white and colored marble.” The same fecundity that characterized Southern California’s citrus belt blessed the cemetery with groves of “orange trees…yellow with their ‘apples of gold,’ complementing the sway of palms and pepper trees.” Flowers, too, “smile[d] above the silent sleepers.”

Rosedale’s founders had reason to believe in the permanence of their vision. They were, after all, planning for eternity. The trade magazine Monumental News wrote in 1908 that Rosedale boasted one of the best collections of California flora of any regional park. It was a triumph over burial grounds of the past, “where weeds flourished and where trees and flowers withered and died for lack of care.”

The landscape looks and feels different today. Administrators switched off the water during recent drought years. Patches of green lawn checker plains of dry vegetation, thriving in places where living family members have tended to the earth. The ground is uneven, peppered with fallen and weathered tombstones. Medleys of palm, pine, and oak trees offer some shade, though much of the landscape is exposed to the sun. Monuments show signs of rising damp and creeping moss. The cemetery remains elevated and walled off from the surrounding boulevards.

I persuaded my husband to visit J.M. Guinn’s gravesite on Halloween. The date was coincidental, although I welcomed the idea that others (among the living) might be wandering the grounds. A security guard flagged us down as we ascended the driveway. He surveyed us, asking if we were there for family or for entertainment. I hesitated a beat: “Family, of course.” He studied me a moment, then gave us permission to photograph our family gravesite, but no others. “This is not a place for tourists,” he warned us, “and people are looking for trouble today.” We assured him we meant no disrespect, but I wondered how closely we’d be watched. I asked for a map, but he didn’t have one and couldn’t point us to the section where Guinn was buried. “Good luck,” he said, waving us forward. We were on our own, looking for a single grave among tens of thousands.

I weighed the ethics for a moment. True, the ancestors I sought were historiographical, not familial. I was standing on private (and sacred) property, but my subject led a public life. A civic life. He, too, had asked questions of the dead. I decided he would forgive my curiosity. There was an intimacy in this ritual of research that exceeded my usual experiences in an archive, and the pandemic pushed me to pursue it.

Without a map or roadside markers, we drove blindly through the cemetery. As we neared the northeast corner of the site, we noticed a collection of graves dating to the late 1910s. Since Guinn died in 1918, this seemed a good place to start. Our only guidance was an undated photo from the crowdsourced website “Find a Grave.”

I stepped gingerly through this section, making note of familiar names. Nearing a uniform collection of headstones (marking the graves of Spanish-American War and World War I casualties), I noticed an older mexicana in my peripheral view. She showered water on a thirsty corner with her own garden hose. Her purple handcart was filled with dozens of orange cempasúchil. Flor de muertos or marigolds, the flower of the dead in Mexico and elsewhere in Latin America. She labored in this section alone, watering the graves of her beloveds.

All around us, others carried out maintenance work. Much of it was seasonal: watering burial sites, turning the soil, spreading fertilizer and grass seed, and laying flowers. Some repairers came with their families, gathering in small (masked) groups. They brought picnic baskets and blankets, inviting their ancestors to join them for a meal in honor of Día de Muertos, also known as Todos Santos. A few worked alone; these solitary repairers were all women. I recognized the rituals they were performing, having tended to my own ancestors’ graves in this way.

Rosedale Cemetery, now operated by Angelus Funeral Home, faces a fate similar to thousands of historic cemeteries across the U.S. Its maintenance costs outstrip the financial resources of its owners, and fewer living people are making a habit of repairing the land themselves. It seems an inevitable cycle of forgetting.

Mexicans and other Latinxs, however, still travel to Rosedale to remember. In late October and early November, the living assemble offerings for the spirits of the dead: candles, flowers, images, food, and other personal tokens. We craft altares in private homes and in parks, plazas, and, yes, cemeteries. While much of this intimate ritual occurs within families, activists and storytellers often dedicate public ofrendas to those who died unjust deaths.

Last year was different. The pandemic devastated Latinx communities, leaving more people to mourn with fewer able to gather in remembrance and community. Nonetheless, the landscape bore traces of this ritual as we strolled the grounds. The Santa Ana winds had calmed, but they still carried the aroma of copal across the cemetery. We wandered for an hour before we stumbled upon Guinn’s family headstone. His headstone was cast from rough granite, the names James Miller Guinn (1834-1918), Dapsileia Marquis Guinn (1844-1929), and Edna Marquis Guinn (1885-1910) inscribed on one of its faces. The other face bore the names Mabel E. Guinn (1875-1968), Howard J. Guinn (1886-1958), and John Joseph Guinn (1924-2012). Each member of the Guinn family also had their own lawn plaque, marking individual burial sites.

The generational connections between the Guinn family and Rosedale struck me. I noticed, when returning to Find a Grave, that his descendants (including John Joseph Guinn) had left virtual flowers and messages for him on the site. He was clearly beloved, a source of family pride, and an ancestral anchor. His children, grandchildren, and even great-grandchildren treasured their roots in Los Angeles. Standing there, I felt like an interloper, and my view began to soften.

I wondered, for example, if the Ohio-born Guinn experienced homesickness and if his crusade for institutional remembering was a salve. I thought of the affective reasons why a person longs for the past, particularly a person who makes a life far from where they spent their formative years. I felt for him, remembering that he found his way to California as a broken young man, all-too familiar with the fragility of life and community.

Standing at his grave also reminded me of the ways that our imprints on the land outlive the spans of our waking lives. What a humbling experience to meet him here in conversation, 102 years after his death, still asking some of the same questions about landscapes, memory, and storytelling. I imagine he, too, would have pondered the archival potential of this craggy cemetery.

In many ways, Guinn was wrong about what Los Angeles’s future held. There he was, buried among other settlers and immigrants, in a mostly Latinx neighborhood, where rituals of remembrance continued to travel across the U.S.-Mexico border. Mexican people, history, and culture persisted, despite an abundance of nineteenth-century declension stories.

But did he mean harm? Despite being entangled in racist systems, did he celebrate violence, loss, and despair? It’s hard to know. His commitment to telling the truth was no less earnest than my own. Perhaps the only certainty either of us holds is that a future generation will know more than we knew in our own time and will, inevitably, correct us.

***

For now, I must reckon with what I share with Guinn. I call greater Los Angeles my home because my ancestors migrated to this region from Mexico and Ohio in the last century. My blended background means I am at once his settler kin and one of the Mexican American scholars he never imagined. My search for fragments and lore might have given him pause. Unlike the amateurs of his day, I am trained as a preservation practitioner and have helped maintain the very memory tools that need unmaking. I have an obligation to be, as Lorenzo Veracini suggests, a “worse settler.”[10]

Neither Guinn nor I descend from the ancestral stewards of this land. Yet we share an attachment to it. If I want my scholarly contribution to unpack what we might learn from the people who resisted Guinn’s constructions of civic memory in the past – to bring us a bit closer to reparative acts of remembrance – then I have to stick with Guinn a bit longer.

This also reflects the aspirations of the city’s Civic Memory Working Group. It is easier to topple symbols of the past that fail to serve the public interest than it is to repair the pain real people caused and felt, or to remake unjust systems. If we are to conceive more equitable processes for commemorating our shared past, we must challenge the colonial practices we’ve assumed responsibility for. We ought to unravel Los Angeles’s settler fantasies, reimagine the meaning of “expertise,” and disassemble the social, economic, and political barriers that constrain what we remember and where. We need a different definition of justice than the ones we have inherited. Dissonance, rather than concurrence, ought to guide us.

At this moment, the potential for transformation of our city’s memory, its conscience, and its cultural fabric is stunning. Let us be bold enough to encounter our ghosts.

Laura Dominguez is a PhD candidate in the Department of History at USC. Her dissertation examines the ways racialized Angelenos repaired and maintained heritage practices in nineteenth and twentieth century Los Angeles. She holds a bachelor’s degree from Columbia University and a master’s degree in historic preservation from USC. She previously worked in advocacy and education for the Los Angeles Conservancy and San Francisco Heritage and is a founding board member of Latinos in Heritage Conservation.

[1] Laurajane Smith, Uses of Heritage (London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2006), 2.

[2] Christopher Hawthorne, “The River, the Freeway, and the Garden,” in Past Due: Report and Recommendations of the Los Angeles Mayor’s Office Civic Memory Working Group (2021): 5, https://civicmemory.la.

[3] J. M. Guinn, “Two Decades of Local History,” Annual Publication of the Historical Society of Southern California and of the Pioneers of Los Angeles County 6, no. 1 (1903): 47, doi:10.2307/41169606.

[4] Merry Ovnick, “Looking for the Founders of the Historical Society of Southern California,” Southern California Quarterly 97, no. 2 (2015): 159, doi:10.1525/scq.2015.97.2.156.

[5] Guinn, “Two Decades of Local History,” 42.

[6] J. M. Guinn, “Historic Houses of Los Angeles,” Annual Publication of the Historical Society of Southern California, Los Angeles 3, no. 4 (1896): 63, doi:10.2307/41167604.

[7] John Mack Faragher, Eternity Street: Violence and Justice in Frontier Los Angeles. (New York: W W Norton, 2017).

[8] Diana Taylor, The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003), 18–20 and Yesenia Navarette Hunter, “Entangled Histories of Land and Labor on the Yakama Reservation in the 20th Century,” PhD Diss., forthcoming.

[9] David Torres-Rouff, Before L.A.: Race, Space, and Municipal Power in Los Angeles, 1781-1894 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013), 194–95.

[10] Lorenzo Veracini, “Decolonizing Settler Colonialism: Kill the Settler in Him and Save the Man,” American Indian Culture and Research Journal 41, no. 1 (January 1, 2017): 2, doi:10.17953/aicrj.41.1.veracini.