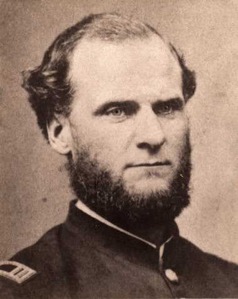

Capt. Joseph Deverell, 108th New York Volunteers, ca. 1862

The first Deverell in my line came here with the famished. Joseph Deverell, from County Laois, arrived in Canada in 1849 or 1850 and made his way south to Rochester, New York. Alongside as many as 3,000 of his countrymen, he worked on the Erie Canal. He probably did manual labor on that waterway transit system stretching the four hundred miles from Albany to Buffalo. But he may have done other work, as it seems that Joseph could read and write, which would likely have distinguished him from many a famine Irish immigrant.

Joseph Deverell joined the New York militia. He may have gone to a militia rendezvous in the mid-1850s where the orator of honor was famed military historian John Watts de Peyster, coincidentally a many times great uncle of my wife. By 1860, Joseph had become a Rochester lawyer.

At the onset of the Civil War, he organized the all-Irish Company K of a Union regiment out of Rochester, the 108th New York volunteers. The 108th saw heavy combat in twenty-eight battles. After one battle, Joseph was cited for bravery by his commanding officer. He was grazed in the head at Gettysburg, where the 108th suffered more than fifty percent casualties killed or wounded.

Joseph was shot in the thigh at Cold Harbor, the 1864 battle in which General Ulysses Grant, knowing he had more men than General Lee, sent wave after wave of Union troops at emplaced Confederate artillery and infantry positions. He would later regret some of his actions that day.

For Joseph, the war was over. He came home to Rochester and started a brief career as a lawyer.

Joseph Deverell’s service, either his leg wound or the tuberculosis he (like so many soldiers and others in the nineteenth century) may have contracted, eventually cost him his life. But not before he fathered three sons. One died young — maybe tuberculosis got him, too. A son who lived was named Robert. Another, who was a house painter and maybe Rochester firefighter, was named William. He had a son, William, who was in the Navy in World War One and became a chemist. His son, William, became a physician and a career officer in the US Air Force. His son, William, is me. We have Joseph Deverell’s ball and cap pistol, his name carefully etched into the metal of the butt plate.

I’m Irish, and I live in Los Angeles. That’s a miniature diaspora, in a single case of one. Joseph was Protestant of Huguenot background — the name was probably at one time Devereaux — but my father and his father and probably the father before that were raised Catholic in working-class Rochester. Half my cousins are Italian Catholics, from a family of ten kids. They all have Deverell as a middle name; their surname is Bianchi. My father attended Thomas Aquinas High School in Rochester and remembers visiting family graves, Joseph Deverell’s among them, in Mt. Hope Cemetery, where the likes of Frederick Douglass and Susan B. Anthony are buried.

My dad left the church in 1956 to marry my mom. They will celebrate their 62nd anniversary in a few months. She was Presbyterian, and they settled on Episcopalian, which is how I was raised. His leaving the Catholic Church was not especially well received by some friends and family.

Let’s broaden our frame briefly. It is well known that the famine Irish settled mostly in the mid-Atlantic and Northeast, then the Midwest, the West, and less heavily in the South, though they are there, too, especially if we stretch the clock to get at the post-Civil War industrial rebuilding of the New South.

New York, Massachusetts, Illinois, and Pennsylvania are the most Irish of states since about 1850, with fully a quarter of New York City and Boston being Irish born at the start of the Civil War. Interior migration from the eastern seaboard increases late in the century, as a way to try to deflect the urban poverty and destitution the Irish encountered. The mining West and the railroad West called to the Irish. The Rocky Mountain spine of mineral and metal excavation is very Irish by 1900. Butte, Montana is the most Irish place in America and probably still vies for that title unto today.

California has long been attractive to the Irish. That attraction leans to the north, with the Gold Rush and early railroading and a good port having a lot to do with it, as well as an early and firm implantation of Irish Catholic institutions. Already by 1870, there are 54,000 Irish born in California. What’s interesting about that is that only half these are in San Francisco — I would have thought far more — the remaining 25,000 or so must have been concentrated in the gold fields or Sacramento; Los Angeles is yet too small, though they are here. And they keep coming, probably by way of trying to make it first in gold hunting, then draining off to San Francisco, then coming South as Los Angeles began, slowly at first, then much more ambitiously, to stretch its metropolitan shape and ambitions – goals that demanded infrastructure and the labor that went with.

In terms of the backs and shoulders of Los Angeles growth, Irish laborers played important roles. We just haven’t dug deeply enough into the historic record to find them in the aggregate. Before the Mexican Revolution of 1910, Mexican descent laborers are relatively modest as represented in the laboring ranks, and the Chinese generally get shunted off to feminized labor as cooks, launderers, domestic help, often by the blunt end of a Hibernian cudgel. And of course Los Angeles is where Irish American trades-unionists-turned-saboteurs, the brothers J.J. and J.B McNamara, blew up the Los Angeles Times in 1910.

Recent archeological and historical work in the laboring camps of places like the Mt. Lowe Incline or the Los Angeles Aqueduct reveal Irish or Irish American men working for, in the case of the aqueduct, Ireland’s own William Mulholland.

Mulholland’s rise to authority is unusual in the West in a few respects. He’s just a bit too young, by about a decade or so, to have been dragged into the Civil War. He was autodidactic as to hydrology and engineering, and he rode his native intelligence up the ranks of a growing Los Angeles in need of water and the systems to hold it and move it.

Irish or Irish American counterparts, again just a bit older, are likely to have had Civil War service. There are perhaps 200,000 Irish in the war, on both sides, with a not insignificant chunk coming from California itself. The war’s effect would likely have been profound for many if not most of these men: officers or enlisted men taking military leadership or discipline into post-war jobs in industrial or mining America, many finding their way west, many staying in uniform. One of six of Custer’s ill-fated 7th Cavalry is Irish.

Southern California is, by the 1880s, heavily railroaded. We wouldn’t have to look far to find Irish in that metal web, many of whom had come out of the war and skedaddled west.

And of course many come west because the war hurt them. The most Irish place in Southern California in the late 1880s is almost certainly not a church, a neighborhood, or a school. It has to be the Soldier’s Home in Westwood, a place for destitute, wounded, or otherwise hurting veterans of the Mexican, Civil and Indian wars. How they lived and died, how they navigated their later years here on the coast, with so many of them likely born into famine Irish years, remains largely unknown and unstudied, as far as I know. But I know that they are there.

That theme of escape tinged with convalescence or maybe a kind of postwar redemption hits home, hits a diasporic nerve. Like my father, my middle name is Francis. We are named for my father’s uncle, John Francis Daly, the brother of my dad’s mother, Helen, for whom my daughter is named. Francis was, by all accounts, the darling of the family: boisterous, funny, intelligent, one generation removed from the Irish countryside, raised in the Rochester ward in a seemingly tight-knit Catholic family. Then comes the First World War, and off Francis goes, scooped up by Selective Service and the draft. He may have been a cook in his unit, but, given the battles he was involved in; he was probably a cook with a rifle.

John Francis Daly, Rochester, ca. 1916

Francis came back, back to Katherine, the young wife and shoe factory worker he had married in 1915, when they were both twenty-one. When Francis shipped out, Katherine moved in with my grandmother and her parents.

Katherine Hamell, in later years

My father remembers dressing up in Francis’s doughboy uniform that had been neatly ironed, folded and boxed up in the attic. “Up in the attic, turn left, and there was a box with a uniform in it,” my dad remembers.

But something was wrong. Francis came back following combat in France, the Argonne Forest, Moselle. He was honorably discharged in the spring of 1919. But he didn’t stay in Rochester, he didn’t stay in that home on Main Street. In fact, he disappeared, sometime around 1919. The family didn’t talk much about him. My father remembers very little said about Francis. The young wife stayed in her in-law’s home. And, despite that khaki uniform in the attic, a family story grew up around the missing Francis: he had been killed in the Great War, the story went, an Irish working-class Rochester hero.

The lore is wrong, the story more complex and mysterious. Francis dropped out of sight, but he did not disappear. He went west. He changed his name to Harry Wheeler and disappeared in plain sight, 2,300 miles away.1

Francis (now Harry) moved here to Los Angeles. Around 1920, he married a Mexican or Mexican American girl, Mary Louise Saenz, either in Mexicali or Tijuana, just over the border. I’m wondering if they met in Mass. I’m wondering if they married in Mexico because Harry was perhaps still married. I’m wondering if divorce, in that family, in the Catholic Church of that era, was impossible; desertion and disappearance might have seemed easier.

Mary Louise Saenz, ca. 1920

Harry and Mary Louise lived in El Monte, about twelve or thirteen miles from where his namesake – me – lives with my wife, our son John, and our daughter, Helen. They had three children: John Joseph Wheeler, Eugene Francis Wheeler, and Lorraine Louise Wheeler. Besides his sister, Helen, (my grandmother), John Francis Daly had a brother, Eugene, born in 1897.

Francis had at least two jobs. One, he worked as a baggage and mail handler for the Pacific Electric Railway, that agglomerated trolley system monopolized by Henry Huntington, he of the library and art gallery and botanical gardens that bear his name and which define the professional lives of both my wife and myself.

And two, Francis ran booze during Prohibition, with his Mexican father-in-law, a lard maker for a meat packing company, on the east side and occasionally right into the clutches of the law and directly into incarceration. Perhaps true to family legend regarding his generosity, Francis seems to have taken the fall at least once for his father-in-law when both got snared in rum running nets.

Harry Wheeler, ca. 1930s

Harry Wheeler and Mary Louise Saenz Wheeler, ca. 1940

Finding Francis was the result of maybe fifteen phone calls and as many hours on the internet. Finding Francis was part of a DNA story that connected my father to second cousins he never knew he had, the offspring of the man he was named for.

Finding Francis is ever an Irish in Los Angeles story. War and its costs, its ravages. Work. The Church. The upbuilding of Los Angeles with its Irish laborers. Drink.

Finding Francis is a thread in an as yet unwoven tapestry of the Irish in Los Angeles. It’s not that they weren’t – or aren’t – here. They were, they are. We just have to remember that history is murky and that historical actors — especially everyday people — challenge us to find them, both because of what they may have wanted in terms of living below scrutiny but mostly because everyday people are usually in history’s shadows whether they wanted to be or not.

Francis came here. He probably wondered if he’d be found or found out. Maybe not. He may have wondered if he’d be understood. He’s one in a diaspora. One in a thousand, ten thousand, more. They are all out there. Finding Francis, finding a Francis, is something we all can do.

William Francis Deverell, Jr.

1. An historian friend of mine noted that Francis belonged to one of the last generations of Americans who could pretty easily disappear if they wished. And of course disappearing into the West is an old story by the time Francis does it.↩