The Aerospace History Project, under the Huntington-USC Institute on California and the West, is an effort to document the history of the aerospace industry in Southern California and the economic, cultural, and physical effects on the region and beyond. The project collects the papers and oral histories of key individuals and institutions across the aerospace industry, creating a permanent, central resource.

The Director of the Aerospace History Project, Peter J. Westwick, is Assistant Research Professor in the History Department at the University of Southern California. He received his BA in physics and PhD in history from UC Berkeley, and has taught at Yale and Caltech. His research focuses on the history of science and technology in the twentieth century U.S. He is the author of several books including Into the Black: JPL and the American Space Program, 1976-2004, and The National Labs: Science in an American System, 1947-1974. He is also editor of Blue Sky Metropolis: The Aerospace Century in Southern California.

In the following interview, Peter reveals how he became involved with aerospace history, some of the most interesting things he came across while working with the Aerospace History Project, and current projects.

ICW: Tell us a bit about your background and how you came by your interest in science and technology.

Peter Westwick: When I was a kid I got my hands on some popular books on astronomy and astrophysics and was transfixed by the images and descriptions of the universe. So when I went off to college at Berkeley I decided to study physics. But I also always really enjoyed reading history, and I also liked writing. After my undergraduate degree I was working as a physicist in industry, and I discovered that there was actually a field, the history of science, that combined my interests – and that Berkeley had a strong program in it, with one of the leading historians of physics. I decided to give history of science a try in grad school, and I was hooked.

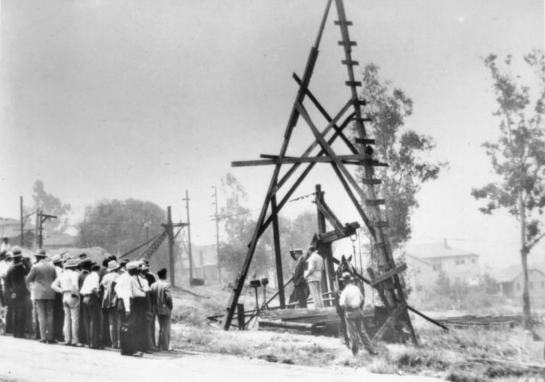

French aviator Louis Paulhan makes record-breaking flight to 4,600 feet in 1910. The balloon in the background advertised the Los Angeles Examiner, which helped sponsor the 1910 LA Air Meet. (photCL Pierce 6298, C.C. Pierce Collection of Photographs, The Huntington Library)

Describe the Aerospace History Project: what is it, how did it come about, and what is your role?

Westwick: The project started when Bill Deverell and I were both at Caltech. I was working on a history of JPL and wanted to situate it in the context of Southern California, so I went and talked to Bill. We both realized the importance of SoCal aerospace to our respective fields – me, history of science and technology; Bill, California history – and also that few archival sources existed to support scholarly research. We also both recognized that a window of opportunity was closing: because of recent mergers and relocations a lot of corporate files were being shredded or tossed; and many individual pioneers were fading from the scene, so we were losing the chance to record their memories and save their papers. Then Bill got the offer to come to USC and ICW, and we recognized another opportunity: the Huntington Library, with its strengths in history of science, California, and business history, was a natural home for the archive. That brought Dan Lewis on board as the third member of our little triumvirate. Dan knows the archival landscape and also the practical issues of acquiring collections. My instinct as a historian is to save everything, and Dan often has to remind me that we have finite space and resources, so that we have to make decisions. Bill knows everyone in the L.A. area and is constantly coming up with new connections to people or collections. Bill has also been instrumental in finding funding, and also in finding creative avenues for outreach, for instance through a series of great programs for high-school teachers. He reminds me that it’s not enough just to save stuff; we also then need to help push that history out to the scholarly community and the general public.

My role is to provide the intellectual connection to aerospace history and understand the needs and opportunities of researchers. I help evaluate potential collections and also handle the oral histories; it helps here that I can speak the language, at least a little, since I have some technical background. I’ve also mentored the two postdocs we had under an NSF grant (I’m happy to say that they have since landed jobs at Harvard and the National Air and Space Museum). One of these postdocs, Matt Hersch, worked with me on an exhibit at the Huntington in fall 2011, mostly using materials from our collections, that attracted about 25,000 visitors. We had so many people come up to us in the exhibit and say that they had friends or family who had worked in aerospace – or that they themselves had worked in it – and thank us for recognizing the importance of this history. That’s a rare and very gratifying sort of feedback for historians.

Tell us some things about the book you edited on the aerospace industry in Southern California.

Westwick: When Bill, Dan, and I first started planning the project we had the idea to start off with a conference, as a way to survey the landscape, to figure out what we already knew and where research was nee ded. We held the conference at the Huntington in 2007, and we got such a great response – not only from the over a hundred people who showed up, but also from people who heard about it through the media coverage – that we decided to bring the material to a wider audience through an edited

ded. We held the conference at the Huntington in 2007, and we got such a great response – not only from the over a hundred people who showed up, but also from people who heard about it through the media coverage – that we decided to bring the material to a wider audience through an edited

volume of papers. The book wasn’t just a

collection of conference papers, though, since we brought in several more contributors. Bill also had the great idea to include a photoessay, and I had a lot of fun sifting through the Huntington’s photo collections for a few gems to illustrate themes of early aviation.

We really tried to highlight the diversity of topics and historical approaches, so the papers look at aerospace intersections with Hollywood, architecture, labor, women, the environment, and so on. It’s really an eclectic but, we think, eye-opening perspective on the many ways aerospace shaped Southern California, and vice versa.

Are there particularly important collections that you have helped bring in to the Huntington archives, and what collections are still “out there” that you may know about and are interested in drawing into the archive?

Westwick: Thanks to generous advice from Sherm Mullin, a former head of the Skunk Works, we’re particularly strong on Lockheed: we have the personal papers of Clarence “Kelly” Johnson, the Skunk Works’ founder, and Ben Rich, Johnson’s successor, and so have a wealth of material on the U-2, SR-71, the F-117A, and other celebrated planes. We also have several thousand photos on pre-World War II Lockheed from Harvey Christen, one of Lockheed’s first employees, and a systematic collection from Willis Hawkins, a key designer and manager. We also have a very substantial collection of historical files from Northrop Grumman, and the papers of Tom Jones, who was head of Northrop for three decades. We have the papers of Bud Wheelon, a major figure at Hughes and in the national-security and space program in general. We also just received the papers of the Planetary Society, which was formed here in Pasadena in 1980 and has been probably the most important public-interest group for space exploration ever since.

But however we much we collect, we are always driven by the knowledge that so much more remains out there to preserve, and that a lot of it will be lost if we don’t act.

What are some of the most interesting things you’ve found in the archive?

Westwick: One of the more interesting collections is the Al Hibbs papers. Hibbs got his PhD under Richard Feynman at Caltech and like Feynman had insatiable curiosity and diverse interests: he did underwater photography and kinetic sculpture, flew sailplanes, acted in local theater, made an electronic trombone, applied to the astronaut program, contributed to the Biosphere project — all in addition to being an architect of JPL’s early satellite program, and later the “voice of JPL” for radio and TV broadcasts and an important science popularizer. He was just a fascinating character, and his papers are full of interesting twists.

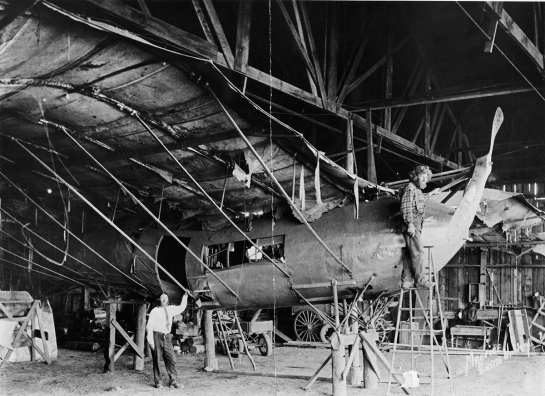

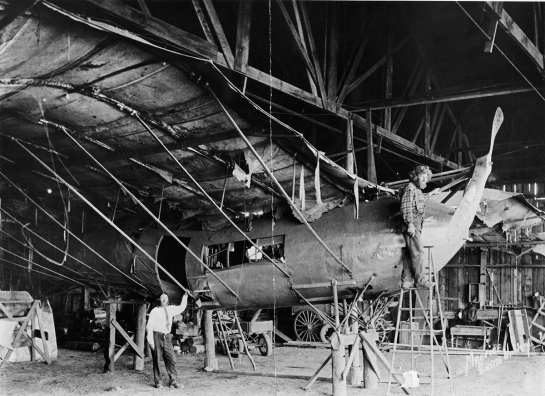

The most unexpected thing was probably an item I ran across while I was cataloging the Ben Rich papers. It was a photo of two bearded gentleman in a barn circa 1907, standing next to a contraption resembling an airplane but of dubious flightworthiness.

The first question was, who were these guys? They turned out to be Charles and Lyman Gilmore, a couple brothers up in Grass Valley, California. The airplane was a remarkably ambitious design for the time, just a few years after the Wright brothers: an enclosed cabin in a metal fuselage, big enough for eight passengers, instead of an open wooden framework; a single wing instead of a biplane; and the propeller in front instead of the pusher type used by the Wrights. In fact it was too ambitious – the steam engine wasn’t nearly strong enough to get the heavy plane off the ground. Worse yet, they built the plane bigger than the barn door, so they would have had to take off the wings to get it out to fly.

Lyman Gilmore Jr. and his brother Charles in their barn in Grass Valley, Calif., ca. 1907. Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens.

The second question was, what were these guys doing in Ben Rich’s papers? Of the two brothers Lyman Gilmore was the moving spirit, but he was also an eccentric fellow. He was obsessed with secrecy, and then at one point he stopped cutting his hair and beard and, worse, gave up bathing – not for a few days or weeks, but for years and eventually decades. Rich was fascinated by Gilmore, so much so that the Skunk Works director, a very busy man, took the time to track down all the information he could on him. Now, Rich loved a good story, and he was no doubt drawn to Gilmore as a colorful addition to his collection of anecdotes. But Rich may have also recognized a connection. Granted, there is no path from Gilmore’s barn to the Skunk Works, no technological lineage from his steam-powered plane to Stealth aircraft. But Gilmore still tells us something about aviation and California. It was no coincidence that Gilmore was a gold miner living in the heart of the Mother Lode, or that some of his early investors came from the nearby town of You Bet. Like the original Gold Rush, aviation attracted romantic spirits, people willing to risk failure in the pursuit of their dreams. And Rich was one of them. The first Stealth plane was aeronautically unstable on all three axes, and when Kelly Johnson saw an early model he told Rich, “that goddam thing will never get off the ground.” Both Rich and Gilmore ignored the doubters and pursued their dreams of flight.

Tell us about the oral histories – how can someone use them, and what’s next on that front?

Westwick: We’ve conducted conducted oral histories with a wide range of aerospace figures: men and women, design engineers and shop floor machinists, test pilots and CEOs, from huge firms and small machine shops. These are guided oral histories, conducted either by myself or fellow historians. We’ve done about fifty oral histories and thirty of them are available on-line through the Huntington Digital Library, here.

The rest of the interviews will be posted once they’re through the transcribing and editing pipeline. As with the archival collections, we have far more oral history candidates than we have managed to get to, but we sense the urgency to record as much of this history as we can. There are some fascinating stories in these interviews: personal histories, character sketches, funny episodes, and also illuminating windows on particular issues: African-Americans in aerospace, or secrecy and classification and civil liberties, or antitrust law.

What are you working on these days?

Westwick: My main research project at the moment is a history of the National Academy of Sciences, which is the major honorary society in the U.S. and a major source of science advice to the federal government. The Academy was created in 1863, during the Civil War, and when it reached its 150th anniversary people there approached a few of us historians (Dan Kevles, Ruth Cowan, and myself) about writing a history. I’ve also been working for several years now on a history of the Strategic Defense Initiative, or Star Wars, the 1980s plan for missile defense. I’ve finished most of the research and just need to find time to write it.

When we convened at the Huntington Library in 2009 for a conference on the history of technology in California and the West, we were glancing backwards from a shifting vantage point. Sure, we could look back at transformational infrastructures and the way in which they transmitted power – both literally on the state’s long distance power lines and massive dam projects, and figuratively via the Los Angeles traffic plan and the work of the RAND corporation. We could look back on humbling histories of technological hubris and failure – as with the Helmand Valley Dam Project in Afghanistan. We could see how innovations of the past turned desolate spots into hubs, as with the clocks in the ground somewhere outside Barstow, California, that control many of our GPS devices. We read old technologies as romanticizations of the past – just take a look at San Diego’s Panama Exhibition or the Golden Gate Bridge administrators’ long fight against a suicide barrier, but also discussed historical fantasies of technological futures – such as those of 1970s Californians, fragile and easily usurped when out of place.

When we convened at the Huntington Library in 2009 for a conference on the history of technology in California and the West, we were glancing backwards from a shifting vantage point. Sure, we could look back at transformational infrastructures and the way in which they transmitted power – both literally on the state’s long distance power lines and massive dam projects, and figuratively via the Los Angeles traffic plan and the work of the RAND corporation. We could look back on humbling histories of technological hubris and failure – as with the Helmand Valley Dam Project in Afghanistan. We could see how innovations of the past turned desolate spots into hubs, as with the clocks in the ground somewhere outside Barstow, California, that control many of our GPS devices. We read old technologies as romanticizations of the past – just take a look at San Diego’s Panama Exhibition or the Golden Gate Bridge administrators’ long fight against a suicide barrier, but also discussed historical fantasies of technological futures – such as those of 1970s Californians, fragile and easily usurped when out of place.

ded. We held the conference at the Huntington in 2007, and we got such a great response – not only from the over a hundred people who showed up, but also from people who heard about it through the media coverage – that we decided to bring the material to a wider audience through an edited

ded. We held the conference at the Huntington in 2007, and we got such a great response – not only from the over a hundred people who showed up, but also from people who heard about it through the media coverage – that we decided to bring the material to a wider audience through an edited